Anxiety and depression are increasingly plaguing American adolescents.

Understanding why may help reduce teen suicides—and mass shootings.

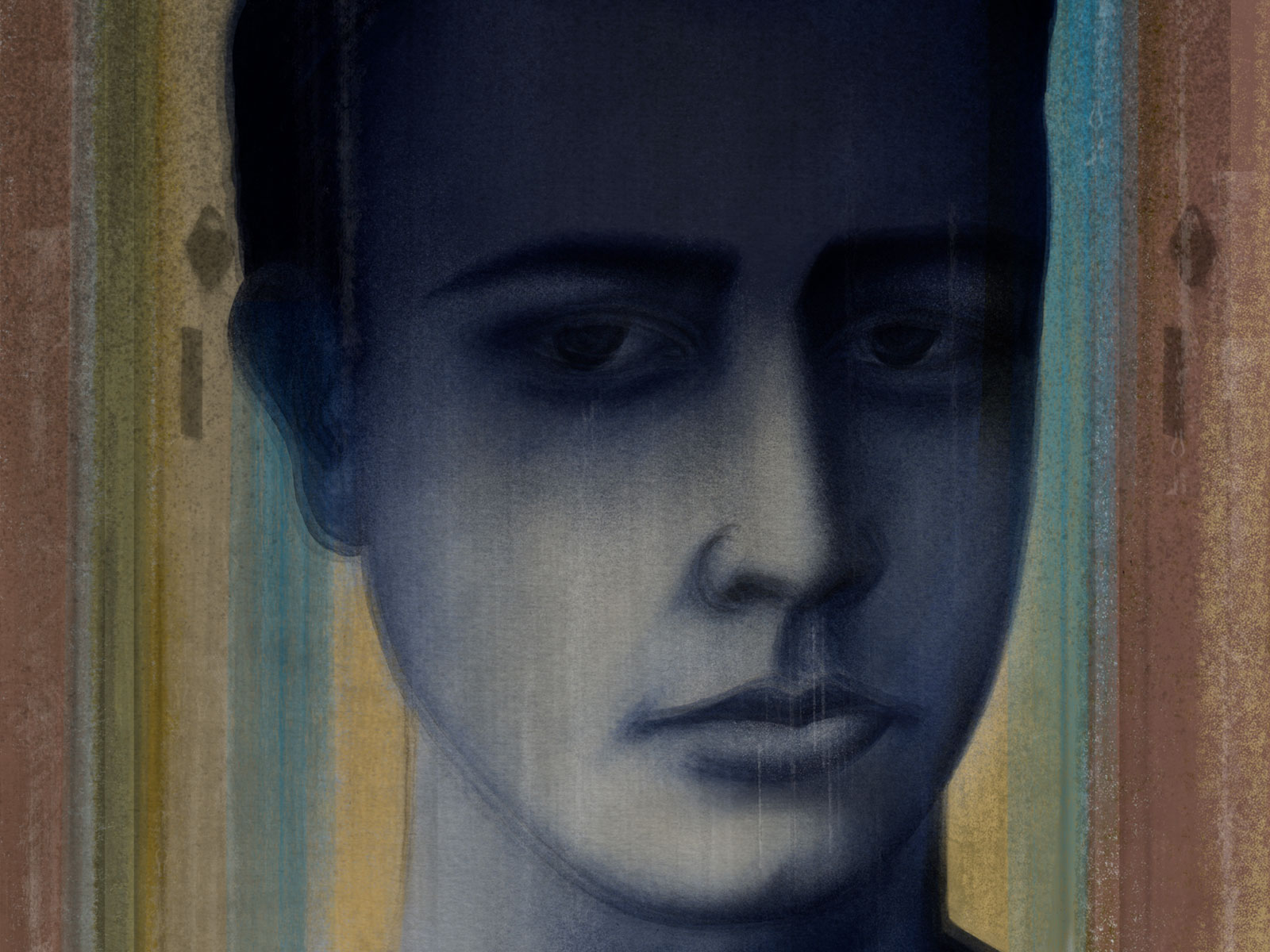

|Hil Abbott used to play lacrosse—he was a long stick middie for Littleton High School—and was also a gifted student. He took multiple AP classes his senior year and got good grades; “the human calculator,” as his friends called him, was admitted to Auburn University’s competitive engineering program in 2016. For years, the blond-haired, quick-to-smile, considerate teenager had been a regular in the youth group at University Park United Methodist Church. And he didn’t go off to college and suddenly stop being a thoughtful and involved son and brother. One night early in his freshman year at Auburn, Abbott got a text from his mother: His younger brothers were throwing a party, and she was struggling to keep it under control. Abbott offered to send over some of his old high school buddies to help settle things down.

Sitting at the dinner table, where they all once shared regular family meals, Abbott’s mom, Courtney Cotton, smiles at the memory. Back then, almost three years ago, “he was a golden child,” she says. As she talks about her son, Cotton’s characteristic dimples come and go, but even they can’t distract from the photo of Bob Marley hanging above her. Captioned with the lyric, “You just can’t live in a negative way/Make way for the positive day,” the image feels incongruous with the seriousness of the conversation. “Hil had balance, he worked, he volunteered,” Cotton says. “We thought we were doing everything right.”

But something wasn’t right. Not long after he last texted with his mother about his brothers’ antics on that late-summer night, Hil Abbott ended his life. He was 18.

Although Abbott died in a dorm room in Auburn, Alabama, his manner of death exemplifies an alarming trend in Colorado. Since 2009, suicide has been the leading cause of death for Centennial Staters ages 10 to 24. Until then, car accidents claimed the plurality of young lives. The change, however, isn’t just a result of decreasing car accident deaths, which have actually climbed slightly since 2012. Rather, Colorado’s death by suicide rate in Abbott’s age group nearly doubled between 2007 and 2017.

Colorado teenagers aren’t alone in this bleak trajectory. In 2017, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics showed that suicide was the second leading cause of death among Americans between the ages of 10 and 34. For the same demographic, the death by suicide rate rose by more than 45 percent between 2007 and 2017.

The root cause of the rise, according to experts, isn’t always clear. However, risk of suicide increases in those who experience major depression or anxiety—and, in this country, teens and young adults seem to be struggling with those disorders more than they ever have. Sixty-two percent of college students nationwide said they had felt “overwhelming anxiety” at some point in the past year, according to the American College Health Association’s fall 2018 survey, an 11 percent increase over five years. And, as reported by the state’s Healthy Kids Colorado Survey, the number of high schoolers who felt sad or hopeless every day for two weeks climbed from 24 percent in 2013 to 31 percent in 2017. “Anxiety and depression are the most prevalent mental health concerns in adolescents,” says Sarah Davidon, director of research and child and adolescent strategy at Mental Health Colorado, the state’s leading mental health advocacy and policy nonprofit. “They’re also often undertreated.”

Whether these increases are a function of a genuine rise in mental health issues among kids or, rather, greater awareness and reduced stigma in reporting these problems is difficult to pin down. Regardless, reports of increasing rates of childhood depression and anxiety have brought adolescent mental health to the attention of policymakers, educators, and health care providers. That, and the fact that these disorders have been repeatedly cited as factors in this country’s recent school and mass shootings.

In the United States, the conventional wisdom suggests that mental health conditions often lead to violence. In reality, only about three to five percent of violent acts can be attributed to someone experiencing serious mental illness. Yet this myth persists—perhaps because of the mental health histories of several of America’s recent mass shooters. The initial reporting on the Columbine killers depicted them as aggrieved victims of bullying. That was not necessarily the case: It was later revealed that both of the boys likely experienced serious mental illnesses. The primary instigator of the mass killing was posthumously labeled by psychiatrists as psychopathic. His partner likely experienced depression. At Virginia Tech in 2007, in Newtown, Connecticut, in 2012, and at Arapahoe High School in Centennial in 2013, young men with histories of mental health issues killed dozens of students and staff. Last year, a school district report on the alleged Parkland murderer revealed that he showed “clinically significant behaviors of anxiety and depression” at age 10, that he had engaged in cutting behavior, and that he’d told a fellow student about his depression and suicidal thoughts.

To look at every teenager who has bouts of fatigue, who withdraws socially on occasion, or who has mood swings as a potential violent offender would not only be foolish, callous, and stigmatizing, but it would also be largely ineffective. Many people—teenage or otherwise—experience symptoms of anxiety and depression from time to time. Those feelings are normal side effects of being human. But most people are anxious or depressed circumstantially, such as when they’re under stress at work or school, experiencing fear surrounding a life event, or enduring the loss of a loved one. It’s when the feelings persist for extended periods of time and are severe enough to impact or limit major life activities that mental health experts consider them disorders.

Child and adolescent psychologists also frequently point to the advent of the smartphone—generally pegged to the introduction of the iPhone in 2007—as a watershed moment in teenage mental health.

It is in this realm—where symptoms linger long enough and are severe enough to constitute a serious health concern—that mental health practitioners say too many of our children subsist. It is also why, in 2017, Colorado’s attorney general commissioned a study titled “Community Conversations to Inform Youth Suicide Prevention.” In an effort to better understand trends and patterns related to young people taking their own lives, the examination explored four Colorado counties—La Plata, El Paso, Pueblo, and Mesa—with recent clusters of youth suicide as well as historically high rates of suicide across all ages. The report’s executive summary cites poor employment and struggling economies as influences in the overall rate of suicide but points to social media, technology, underdeveloped coping skills, and a lack of resilience as risk factors in kids.

These findings align closely with the three stressors many clinicians, educators, and researchers point to when discussing why kids today feel so mentally overburdened: social media, mass shootings (including those in schools), and parenting styles that place performance pressure on kids while simultaneously underpreparing them for how to overcome failure. While these issues may not sound new to anyone who watches the Today Show or reads the Washington Post—the mainstream media has covered these stressors extensively—it’s easy to forget that Facebook is just celebrating its 15-year anniversary this year and Instagram is less than 10 years old; that the frequency and intensity of active-shooter drills in U.S. schools has only increased over recent years; and that the term “helicopter parent” wasn’t coined by child development researchers until 1990. In short: These inputs are still new for our society. So new, in fact, we might not yet know their full impacts.

Child and adolescent psychologists also frequently point to the advent of the smartphone—generally pegged to the introduction of the iPhone in 2007—as a watershed moment in teenage mental health. In her book iGen, Jean Twenge, a psychology professor at San Diego State University who studies adolescent mental health and how psychology differs across generations, explains that rates of smartphone adoption have neatly correlated with an increase in teen depression. “The arrival of the smartphone has radically changed…teenagers’…mental health,” Twenge wrote in a story for the Atlantic. “These changes have affected young people in every corner of the nation and in every type of household.”

Dana Charatan, a Boulder psychologist and psychoanalyst who treats adolescents (many for clinical depression and anxiety), agrees. She believes smartphones and the round-the-clock access to social media they proffer contribute to an environment in which kids are “constantly expected to be ‘on’ all the time,” she says. “Phones have made it very difficult for kids to have downtime; there’s not a lot of space for kids to quiet their minds.” Furthermore, kids often compare themselves to what they see of their peers on social media, which Charatan says may contribute to feelings of isolation and loneliness.

Whatever stressors are causing teens’ mental health woes, clinical psychologists say the problems appear more severe than in the past. Charatan has seen noticeable changes among the patients who sit on the couch in her office since she went into private practice in 2011. “The levels of anxiety and panic and [certain forms of] depression” have increased, she says. She’s also seen a rise in self-injury. Denver psychologist Sarah Haider says she, too, is seeing more severe anxiety among kids, including behaviors like refusing to go to school. Some of her patients today are simply not functioning. “Before it was, ‘I need treatment for my symptoms,’ ” she says. “Now it’s helping kids to get out of the house, kids having panic attacks, manic tantrums. Their anxiety gets triggered, and they literally feel as if they’re going to die.” Or worse, they want to die—and, in some extreme cases, want to take others with them.

Colorado is ill-equipped to handle these unsettling trends. Not only was its suicide rate for 15- to 19-year-olds nearly double the national average in 2017 (per the CDC), but the state was also in the bottom third for Mental Health America’s youth rankings, indicating a high prevalence of mental health issues and lower rates of access to care for children. Colorado is emblematic of a nationwide problem; the country is facing a dearth of child psychiatrists. In the Centennial State, not one county has what is deemed an adequate level of child psychiatrists by the American Academy Of Child And Adolescent Psychiatry.

In addition, the state’s schools suffer from an extreme shortage of psychologists. As of late 2017, they have an average of one per 956 students. The recommended ratio ranges from one per 500 to one per 700. For those who subscribe to the outdated view that school psychologists sit in windowless rooms and do quiet evaluations of students with special education needs, the skewed ratio might seem to be a minor issue. It isn’t. Not only do schools need on-site psychologists to offer in-the-moment therapy for the increasing numbers of kids struggling to get through the day, but they also play a critical role in threat assessment, a prevention method recommended by the FBI, the Secret Service, and the Department of Education for identifying students who may be a danger to themselves or others. Experts in threat assessment, such as the University of Virginia’s Dewey Cornell, say that evidence-based models suggest school mental health professionals are an integral part of assessing students and identifying appropriate interventions.

As such, it would seem like Colorado, which has suffered through several high-profile shootings as well as possible suicide contagion at some of its high schools in recent years, would find funding for school-based mental health care professionals and programs. Instead, state government has opted to address issues further downstream. During the 2018 legislative session, lawmakers allocated $59.5 million for schools to spend on safety and security (some of which could be used for threat assessment training, which involves evaluating student mental health) while only releasing $400,000 in grant funding for schools to address suicide prevention.

Rob Stein, superintendent of the Roaring Fork School District, says he isn’t waiting for lawmakers in Denver to make the right decisions. “I’m not against having tighter security measures,” says Stein, whose district includes schools in Carbondale, Basalt, and Glenwood Springs and who recently instituted protocols requiring visitors to all schools to check in at the main entrances and wear badges inside. Over the past few years, he’s also overseen the installation of keyed entryways with bullet-resistant glass at every school. But, Stein says, the evidence is clear that to prevent violence, schools need to invest in restorative practices and developing healthy relationships and healthy boundaries. “There’s a compliance aspect [to school safety],” he says, “but that’s not really where our energies are. We go to, ‘What are we going to do to make a school’s culture more safe and supportive?’ ”

That means drastically increasing mental health resources. With high levels of poverty—about 40 percent of Stein’s students qualify for federal meal assistance—the superintendent grapples with tweens and teens facing all of today’s stressors. He says nearly every kid in middle and high school has a smartphone, and the pressures of being an immigrant have been particularly acute since the 2016 election. The district is addressing these challenges both programmatically, through efforts such as dedicated time in the school day to focus on character-building skills and emotions management, and by cobbling together funds to pay for more mental health professionals.

Managing those efforts alone is a full-time job. And most of the money is “soft-funded” through grants, meaning Stein can’t depend on the dollars being there to pay a school psychologist’s salary next year. Some of these grants come from government agencies as well as from local philanthropic sources, and a small share comes from marijuana tax dollars. Stein calls this “a devil’s bargain,” considering the research showing that pot use by teens contributes to mental health disorders. “Good health and good mental health are imperative for our kids to be able to learn,” Stein says. But he adds that while society has decided “every kid needs an education, we’re not at a point where we think every kid needs health care.”

Hil Abbott was one of those kids who needed help. Unfortunately, no one knew it—not even his mother. Courtney Cotton still wonders what she might have done differently to prevent her son’s death. She tears herself apart examining Abbott’s behavior in the weeks and months before his death. Was he having trouble concentrating? Was he agitated? Did he mention problems sleeping? All of these things can be indicators of anxiety or depression, but symptoms vary. Says Cotton: “I thought there’d be signs.”

Cotton isn’t the only parent to be blindsided by her child’s suicide. And she certainly wouldn’t be the only mother not to notice harbingers of bad things to come. The parents of the Columbine killers have intimated—if not outright declared—that they had no idea their teenage sons were devolving mentally and planning Armageddon at their high school. For some parents, even when they do know that their kid has a mental illness or behavioral issues or a tendency toward violent outbursts, they underestimate the gravity of the situation or they simply don’t know where to go for help. “Some parents are disconnected and don’t recognize the severity of their children’s emotional difficulties,” Charatan says.

She adds that kids have less of an emotional vocabulary and a less sophisticated way of thinking about their feelings than adults, which is why parents and teachers and superintendents need to focus on prevention. Stein recognizes this and works to instill in his Roaring Fork students the abilities to articulate and regulate emotions, to talk about feelings, and to recruit others for help. In psychology circles, building that skill set is often referred to as social-emotional learning. “We want kids to have more understanding of others, a sense of empathy, to be able to work together, and build and manage relationships with others,” Stein says.

Like Stein, Cotton would like to see schools do more to address Colorado’s mental health crisis among teens, right down to their curriculums. “Instead of just sex ed and the human body, let’s learn about emotional health,” she says. Her hope? That giving kids the tools to cope and self-soothe will save another family from the anguish hers has endured.

Ask for Help

If you or someone you know is experiencing a mental health crisis, call 1-844-493-8255 or visit coloradocrisisservices.org.

This story is part of 5280 Magazine’s special issue dedicated to the 20th anniversary of Columbine. Read more about the project here.

NEXT: “People outside this community know about us because of one moment in time.”

How a place beset by unspeakable violence and grief has redefined itself over the past two decades.