Columbine changed more than just how we respond to school shootings.

It also altered how we try to prevent them.

|Twenty years have passed, but A.J. DeAndrea’s memory of April 20, 1999, remains sharp. He was out for a jog when he got the page: Man with gun. Shots fired. Columbine High School. He says that upon arrival at the school he and other SWAT members were told there were six gunmen with hostages inside the 250,000-square-foot school. His voice softens when he says he only fully grasped the situation when he saw the bodies of 17-year-old Rachel Scott and 15-year-old Daniel Rohrbough outside the building.

Inside, he remembers wading through shin-high water from the sprinkler system—triggered by detonated pipe bombs—and being unable to hear anything because the fire alarm and school bell were going off. He can still see the faces of the 18 kids he and his team found hiding near the cafeteria, of the adult staffers they rescued from a freezer, and of the 60 teens they pulled out of a closet in the music room. He also remembers the sensation of rising fear when his team leader reached the library and called for support over the radio. “His voice cracked,” DeAndrea says. “That scared me.”

Since that day, DeAndrea, now deputy chief of the Arvada Police Department, has dedicated his life to training first responders and civilians in the most effective ways to respond in active shooter scenarios. He’s well equipped to do so. After Columbine, DeAndrea responded as a SWAT officer to two other high-profile Colorado shootings: Platte Canyon High School in 2006 and Youth With A Mission in 2007. All these years later, though, he says, “I still wonder, What is our next Columbine?”

That question doesn’t just plague law enforcement agencies, which had to rewrite the response rulebook after Columbine exposed numerous deficiencies to disastrous effect. The query haunts others as well: parents, students, teachers, principals, superintendents, legislators, first responders, survivors, and the loved ones of those who died. Which is why, over the years, we have implemented things like active shooter drills, threat assessment teams, armed school personnel, and anonymous tip lines. Bracing ourselves for the next unthinkable act, however, shows we have, in some ways, become inured to the idea that our classrooms can suddenly become crime scenes.

The truth is that gunmen do not lurk in every high school hallway, and this country’s institutions of learning are still remarkably safe. Some estimates suggest homicides are 67 times more likely to occur outside of schools than inside of them. That figure puts school shootings, as traumatic as they are, in perspective. Still, prevention is paramount. “When it comes to keeping kids safe,” says Mark Hotaling, founder of the Makhaira Group, a Colorado public safety education firm, “98 percent should be preparation. Only two percent should be about reaction. But if you do get pushed into that two percent, you better know what to do.”

The Columbine massacre forever altered our perception of schools as sanctuaries and students as harmless kids—and thus changed our prevention and response tactics. That evolution continues today, courtesy of people like DeAndrea, Hotaling, and so many others, all of whom know better than most what it takes to protect our children.

Table of Contents

- Knowledge Is Power

- Life Line

- Every Precaution

- Critical Line Items

- Must We Protect This Schoolhouse?

- Methodical Acts of Kindness

- What Didn’t Happen

- Strategic Changes

- Taking Direction

- Lockdown Nation

Knowledge Is Power

Columbine-era legislation bestows the ability to share information—but it’s only effective against school violence if we use it.

Could a simple exchange of information have helped avert the murders of 13 Coloradans at Columbine? State lawmakers during the 2000 legislative session thought so. Which is why, equipped with the knowledge that several government agencies had suspicious interactions with the Columbine killers before April 20, 1999, legislators passed bills that formalized channels of communication between law enforcement, district attorneys’ offices, social services, the courts, and school districts. House Bill 1119, which authorized a greater exchange of information between schools and law enforcement, and Senate Bill 133, which required school boards to establish written policies for reporting criminal activity that occurs on school property to a district attorney or local law enforcement, combined to create the potential for a landmark paradigm shift. And it’s worked rather well—except when it hasn’t. Like when a school counselor failed to neutralize the threats of a 14-year-old girl who said she wanted to hit someone with a bat; she later injured two schoolmates with a hammer. Or when educators and law enforcement missed several chances to stop the deadly shooting at Arapahoe High School in 2013.

Incidents like these compelled then Colorado Attorney General Cynthia Coffman to release an opinion 15 months ago reminding educators about the importance of actually using Colorado’s nearly two-decade-old information-sharing laws. Coffman’s 17-page explication focused mainly on the widespread hesitation among school faculties to provide information about worrisome students with outside entities for fear of violating the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), a federal law that protects the privacy of education records. In her communiqué, Coffman, who says the squandered opportunities to prevent Columbine should be enough to compel educators to act, dispatched the myriad misconceptions surrounding the purview of FERPA. She was also clear about this point: Federal privacy laws are not as important as someone’s life. Here, a CliffsNotes-style breakdown of Coffman’s directive.

- Not all student information counts as an “education record.” FERPA does not protect faculty observations about a student’s behavior, rumblings about a student that staff hears from the student’s friends, any information gleaned on social media platforms, or records kept by school security personnel.

- Information that does count as an education record can still be shared, in certain cases. Staff members who have “legitimate educational interests” can liaise, for example, about a student’s uncharacteristic drop in grades. Furthermore, in response to a health or safety emergency, FERPA allows school personnel to divulge almost anything to outside agencies who can help protect students and staff.

- Educators should err heavily on the side of safety. Schools and school employees cannot be sued for alleged FERPA violations. Only federal officials can enforce FERPA—and they generally focus on systemic violations, not honest mistakes.

Life Line

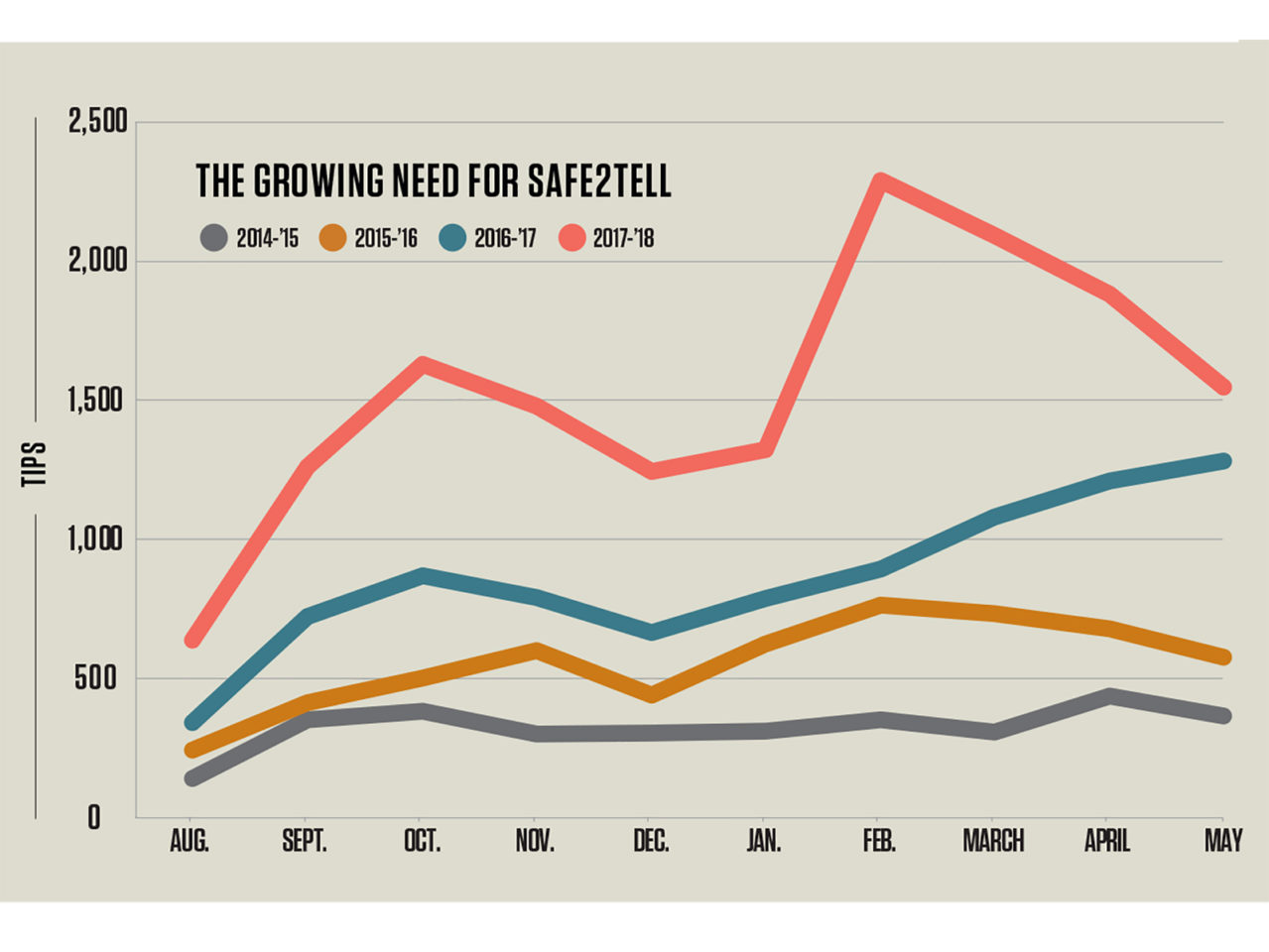

The tips come in every day. Often there are as many as 50 of them, and every single ring of the phone must be treated as an emergency. That’s because Colorado’s Safe2Tell hotline has the unique responsibility of responding to potential threats in Centennial State schools.

Founded in response to the events at Columbine, Safe2Tell was the first tool of its kind in the nation built to prevent violence in schools. Since then, many other states have used it as a model for thwarting their own tragedies. In practice, the program allows Colorado students, teachers, parents, or anyone else concerned about a young person’s actions, safety, or mental health status to register an off-the-record SOS via phone (1-877-542-7233), website (safe2tell.org), or mobile app (downloadable via the Apple App Store or Google Play). The anonymous warnings are forwarded from the Colorado State Patrol—which operates the line and answers the calls—to the appropriate law enforcement agency, the corresponding academic institution, and, if applicable, the school district.

Last year, Safe2Tell took reports on 692 tips about planned school attacks. Over time, however, it’s become clear that Safe2Tell doesn’t just reduce violence; it preserves life. During the 2017-’18 school year, the most popular tip category wasn’t “planned school attack.” Instead, calls largely centered on mental health issues: Reports about “cutting,” “depression,” “bullying,” and “drugs” were at the top of the list. The number one distress call, however, was “suicide threats”—and Safe2Tell responded to all 2,786 of them. “Every time we intervene with students contemplating suicide,” says former Colorado Attorney General Cynthia Coffman, “it’s a significant win.”

Every Precaution

Despite the controversy, some Colorado schools are equipping their staffs with sidearms.

Evan Todd was in Columbine’s library on April 20 and saw what he calls “vile things.” Todd, now 35 and a father, recalls in vivid detail what it was like to talk with the teenage shooters and to believe he was going to die. It’s that memory and mental images of others “lying in their own pools of blood” that has compelled Todd to advocate for a practice that has polarized Colorado and the nation: arming school personnel.

Although it’s illegal in Colorado to bring a firearm to any public K–12—regardless of whether one has a concealed carry permit—state law makes an exception for those with concealed carry permits who also are designated by the school district as security officers. Those “security officers” can be any employees who complete the training. Of the state’s 178 school districts, more than 30 have approved arming faculty. “This is our third year of carrying on campus,” says Keith Yaich, chief financial officer for Bennett School District. “There’s as good a chance as anywhere else that it could happen here.”

As one might imagine, the idea is controversial. Gun control nonprofit Moms Demand Action is a vocal opponent, and the Colorado Education Association, the state’s largest teachers’ union, would prefer to fortify schools with more mental health support. Law enforcement officials worry that first responders to a crisis will struggle to differentiate between gun-toting suspects and gun-toting staff. Even Frank DeAngelis, the principal at Columbine in April 1999, has hesitations. “Even if I’d been carrying that day,” DeAngelis says, “I don’t know if I had the mindset to shoot one of my own students.”

Mindset—or a community’s ethos—is a critical part of the equation. “We’re not Boulder,” says Rose Cronk, superintendent of Woodlin School District, which allows trained faculty to carry. “We’re small and rural, and lots of people are familiar with firearms. The emotional alarm that goes off other places doesn’t go off here.” As Cronk points out, geography plays into the algebra as well. In parts of Colorado, like on the Eastern Plains where Woodlin is located, the closest law enforcement outpost can be 50 miles away. “My police response is going to be at least 30 minutes,” Cronk says. That means a perpetrator could cause untold suffering for an extended amount of time without meeting any resistance.

Todd knows what it’s like to wonder when the cavalry is arriving. On that April day, he wished someone would come to the rescue. That didn’t happen, so, through libertarian think tank Independence Institute’s two-year-old FASTER program, which offers low-cost active shooter and tactical combat medical training for school personnel, he’s using his experience to help armed staffers understand the gruesome scenes they might encounter. “I’ve spoken to several FASTER classes,” Todd says. “These people are saying, ‘I will stand between you and the bad guys.’ That’s heroic.”

Critical Line Items

In 2018, the state Legislature opened its wallet wide for school security with these two grant programs.

School Access for Emergency Response Grant Program

Colloquially known as the SAFER grant program, SB-158 focuses on “interoperability,” a buzzword in school safety circles that harks back to April 20, 1999, when first responders from different jurisdictions couldn’t communicate because their radio systems were incompatible. Some progress has been made in comms among first responders, but this program aims to upgrade the connections between school communication systems and those of first responders. In a crisis, school staff could help police, firefighters, and paramedics respond effectively. Five million dollars annually will be available to applicants over the next six years.

School Security Disbursement Program

Sponsored by several state legislators, including Representative Patrick Neville, who survived Columbine, SB18-269 is a $29.5 million one-time-only grant program designated for building improvements that enhance school security and training for school personnel. The bill’s language is vague about exactly what the money can be used for; however, Chris Harms, director of the School Safety Resource Center, says she hopes schools use it for classroom door locks, bulletproof glass, and secure entryways.

Must We Protect This Schoolhouse?

Mark Hotaling can’t relax. Seemingly incapable of a casual slouch, the former Navy SEAL and founder of firearms training and public safety education company the Makhaira Group has that always-at-attention affect. His comportment is comforting, though, because part of Hotaling’s job is to protect students.

Although nearly every state has passed legislation requiring school safety plans, the relatively new school-security industry is somewhat controversial. The reason: There’s been little research done to show that the pricey suite of available tech—e.g., social-media-scanning apps, bullet-resistant window films, gunshot-detection technology—actually prevents violence.

“I can make your building like Fort Knox,” Hotaling says, “but that’s impractical and expensive. The biggest deal for increasing security is altering a school’s culture. That costs very little.” For a $400 fee, the Makhaira Group provides an assessment that includes suggestions for small changes that can tweak intra-building ways of life and translate into more secure facilities. We asked Hotaling to explain.

A. ID, Please

All school personnel should be identified physically: a red lanyard, say, or a clip-on photo badge. “Staff has to actually wear these things for them to work,” Hotaling says. “If there’s an emergency, it helps first responders to know who is and who isn’t staff.”

B. Meeting Place

Basic safety and security plans are cheap and very effective, Hotaling says. Meeting at the flagpole might not be sophisticated enough, but having blueprints for rudimentary procedures—like lockdowns, lockouts, and evacuations—in place is essential.

C. Key Masters

Keys shouldn’t be given out to just anyone; however, entrusting faculty with the keys they need to accomplish daily tasks encourages them to lock doors they might otherwise leave open out of convenience.

D. Welcoming Committee

Students should enter through the main doors in the mornings, and staff members should be assigned to greet them. Not only does this create a congenial atmosphere, but faculty can also screen for things like overburdened backpacks or kids who are visibly agitated. “This is one innocuous way to deter current students from bringing weapons,” Hotaling says. “It might not catch everything, but it can be a deterrent.”

E. Guardians of the Academy

School personnel and students need to treat their buildings like they would their homes. Tall bushes around the facility should be trimmed back. Window shades ought to be drawn when possible. Doors should be kept closed. “Reminding Mr. Buchanan that he can’t prop open the exterior door to have a quick smoke is more important than it sounds,” Hotaling says. “Someone could see that open door as a vulnerability to exploit.”

F. Window Treatments

If law enforcement officers respond to an emergency, it helps to have the windows numbered on the building’s exterior so someone calling from the inside can easily explain where he—and his 22 students—are sheltering in place.

Methodical Acts of Kindness

A local nonprofit believes compassion can make schools safer.

Darrell Scott’s daughter, Rachel, was the first student killed on April 20, 1999, at Columbine High School. After his daughter’s death, Scott spoke in front of the U.S. House Judiciary Committee’s subcommittee on crime, and his impassioned speech about spirituality, prayer, and the good and evil found in human hearts was widely watched and discussed. Shortly thereafter, Scott founded Rachel’s Challenge, a nonprofit that promotes positive environments in K–12 schools. 5280 spoke with Scott about Rachel’s Challenge’s mission, solutions to the ongoing school shooting epidemic in America, and how he’s doing 20 years on.

5280: How is Rachel’s Challenge different from other anti-school-violence nonprofits?

Darrell Scott: We’re not about school shootings, per se. We focus on solutions, not the problems.

Solutions to what?

Kids feeling like they don’t belong, like they’re disconnected.

Why is that important?

When school shootings happen, we focus, mostly in politics, on our differences, instead of how we can come together. When Columbine or Parkland happens, we fight too much about single, hot-button issues. We rarely talk about the preventive side, which is how the social-emotional growth of our kids can lead to safer schools.

Explain that a little.

Well, there are numbers that say 160,000 kids skip school every day because they’re afraid of being bullied. Now, every kid who gets bullied doesn’t grab a gun and every kid who is violent wasn’t necessarily bullied, but bullying and violence are tied. Neither should be in our schools. We have to teach our kids empathy. We have to teach our kids civility. Rachel’s Challenge’s mission is to awaken compassion and help children connect.

You believe teaching compassion will prevent school shootings?

We know for certain that we have helped prevent seven shootings overall and at least 150 suicides per year. Who knows how many other things we don’t know about? But yes. We have programs—trainings, assessments—that can help a school change its culture to mitigate bullying and violence through kindness and respect.

Kindness and respect were not afforded to your daughter 20 years ago—how difficult was the healing process?

Rachel wouldn’t have wanted my life to be ruined. I try to remember that tremendous things have happened because of her life and because of her death. The first year was hard, but I have otherwise spent 19 of those 20 years celebrating her.

What Didn’t Happen

Lessons in how to stop something before it starts.

Jeff Daniels wasn’t a student at Columbine in April 1999, but the events still affected the course of his life. Early in his professorial career, Daniels, who grew up in Arvada, determined he wanted to research something that would make a difference in the lives of real people. He ultimately decided he wanted to study why kids bring guns to school. Now a professor in the Department of Counseling at West Virginia University, Daniels has been examining violence prevention since 2000. His recent work, done in collaboration with the Police Foundation, based in Washington, D.C., seems to confirm one anecdotal truism of violence prevention in academic settings: The number one way to stop it is for kids to speak up. “Roughly 64 percent of the averted attacks we’ve studied,” Daniels says, “were stopped after being discovered by peers.”

But hypervigilant classmates are only the first step in what should be a well-choreographed course of action to curb a potential crisis, Daniels says. For more than 20 years, the FBI and the Secret Service have encouraged schools to use an evidence-based prevention method called “threat assessment.” Threat assessment is, at its most basic, a standardized process for evaluating a perceived danger, assessing the person responsible for that alleged danger, and making an informed judgment about the probability of the threat being carried out.

Typically composed of school administrators, school psychologists, school resource officers, and local law enforcement agencies, threat assessment teams assemble when someone reports a potential peril. Done correctly, a multidisciplinary team evaluates the seriousness of the threat (is it unrealistic and vague or is it direct, specific, and plausible?), discusses and implements intervention strategies (can a counselor handle it, or should law enforcement be involved?), and follows up with the student in a constructive way after the intervention (experts say disciplinary action alone is ill-advised and can exacerbate the danger).

Twenty years ago, Jefferson County School District did not have a threat assessment program. Today, its two-tiered approach—implemented in 2006—is arguably one of the more sophisticated in the country. And for good reason: “The ghosts of Columbine are here,” says John McDonald, executive director of the district’s Department of School Safety. Threats in JeffCo schools are initially handled by a building-level team; however, if the issue can’t be resolved, it’s bumped up to the district-level team, which has speed-dial access to the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office, the district attorney’s office, and mental health professionals at the Jefferson Center. “We’ve had three [school] shootings in JeffCo,” McDonald says. “We’ve had to learn hard lessons.”

He also says Colorado’s Claire Davis Act, passed in 2015 and named for the sole victim of a 2013 shooting at Arapahoe High School in Centennial, means schools have little choice but to be prepared. The law, one of the few of its kind in the nation, waives governmental immunity, which means school districts can be sued for liability if they fail to use “reasonable care” to prevent “reasonably foreseeable” murders and assaults.

For large districts, finding resources to build effective threat assessment programs is challenging but doable. It’s less feasible for the 127 Colorado school districts with 2,000 or fewer students—which is where the School Safety Resource Center comes in. Created in 2008, it caters to smaller districts, assisting in violence prevention as well as helping prepare for, respond to, and recover from crises. “Most of our services,” says Chris Harms, the center’s director, “are at no cost to schools. They just have to know they can reach out to us. We can help.”

Strategic Changes

Columbine forced law enforcement to adapt to the realities of modern-day active shooters.

The two teenage gunmen at Columbine High School shot their first victim at 11:19 a.m. They turned their weapons on themselves at approximately 12:08 p.m. At 49 minutes long, the horror story they authored was a protracted one. In contrast, the massacre at Virginia Tech’s Norris Hall, eight years later, lasted 11 minutes. The shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in 2012 was over in about 10 minutes. At Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School last year, the murderer dropped his weapon after only six minutes. The discrepancy is not a coincidence; it’s a lesson learned.

Although police were on the scene at Columbine within five minutes of the first gunshots, law enforcement did not enter the building until SWAT arrived and breached the school 47 minutes after the massacre began. “We all wanted to go in,” Denver Police Department Commander Jeff Martinez says today. “But that’s not what you did back then.” Martinez’s orders were to secure the perimeter. Instead, Martinez was among four officers who defied orders and drove down a hill west of Columbine to collect wounded students while taking fire. It was a clear violation of a command—one that later earned the officers medals of honor.

Police departments’ conventional codes of conduct have evolved dramatically since then. Shortly after the events of April 20, law enforcement across the country determined that Columbine was not a SWAT mission. SWAT teams take time to assemble; situations like Columbine required immediate action because the killers weren’t there to take hostages. They were there to end lives. “We knew we had to train our patrol officers to go in immediately,” says A.J. DeAndrea, deputy chief of the Arvada Police Department, who responded as a SWAT officer that day. That switch in tactics—and the associated training, starting in police academy—has evolved over time to allow, if necessary, single-officer entry. Preferably, though, at least four officers would constitute a “contact team,” the sole directive of which is to approach the shooter and stop the bloodletting.

Other aspects of active shooter response have been tweaked as well. Because the contact team cannot pause to assist the wounded, many police departments have partnered with their local fire departments to deploy “rescue task forces.” These squads, comprised of police and fire personnel, follow behind the contact team—which conveys information about casualties they see as they advance—to deliver in-the-field trauma care and to evacuate the wounded to waiting paramedics.

Of course, these adaptations aren’t infallible during a crisis. Without adequate single-officer-entry training, DeAndrea explains, a school resource officer (SRO) can’t be expected to run unsupported into a mass casualty situation, which perhaps was an issue at Marjory Stoneman Douglas, where an on-duty SRO failed to confront the attacker. And, even if an officer is experienced, things can still unravel, as evidenced by the friendly-fire death of a sheriff’s sergeant during a quick entry at an under-siege bar in Thousand Oaks, California, in late 2018. Bottom line: Responding to an active shooter situation means racing toward chaos to help others while risking your own life.

Lieutenant Mark Drajem knows exactly what that feels like. Drajem, who joined Martinez in rescuing injured students from Columbine’s lawn, still chokes up when he talks about that day 20 years ago. The tears come when he says he can’t see the kids’ faces anymore, but that the images of their injuries haven’t diminished over time. He doesn’t know how many students they rescued—he thinks maybe 10 or 12. He does know that he was scared the whole time. “The only good thing about that day at Columbine,” Drajem says, “was that it changed the way we would do things in the future.”

Taking Direction

Colorado’s I Love U Guys Foundation teaches us how to react in an emergency.

Just days after losing their daughter, Emily, in a 2006 shooting at Platte Canyon High School in Bailey, John-Michael and Ellen Keyes founded the nonprofit I Love U Guys Foundation, named for the final text they received from their daughter. After researching best practices, in 2009 the I Love U Guys Foundation released its Standard Response Protocol, a free-to-download, directive-based plan with four possible actions—and a standardized vocabulary—that can be performed during emergencies. According to law enforcement officials, the SRP can affect positive outcomes during crises. Here’s how it works.

If the Order Given Is “Lockout”

That Means: There is a hazard outside the building, like an armed robbery at a nearby bank or even a dangerous wild animal roaming the community

So You Should: Get yourself and everyone else inside the building and lock the exterior doors

If the Order Given Is “Lockdown”

That Means: There is a threat inside the building, like an armed gunman

So You Should: Lock classroom/office doors from the inside, turn off the lights, get out of sight, and keep quiet

If the Order Given Is “Evacuate”

That Means: It’s necessary to move away from a perilous situation to a safer location

So You Should: Follow instructions about where you’re supposed to go, move in an orderly fashion, and keep in mind you may need to evade a threat on your journey

If the Order Given Is “Shelter”

That Means: There is a need to protect yourself from the elements; for example, dangers like tornadoes, earthquakes, or hazmat situations

So You Should: Follow whatever directives you’re given; those could include “evacuate to shelter” (tornado); “drop, cover, and hold” (earthquake); or “seal the room” (hazmat)

This story is part of 5280 Magazine’s special issue dedicated to the 20th anniversary of Columbine. Read more about the project here.

NEXT: Lockdown Nation

Across the country, students are regularly practicing active shooter drills. But are the exercises making kids safer? And at what cost?